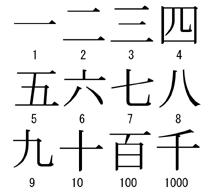

I’ve recently convinced myself that Japanese and Arabic share a relation. While the two cultures are geographically far-flung, the semantic meanings in Arabic of the Japanese words for counting are difficult to ignore, and interesting to explore. Below is a list of Arabic translations of a list of the Japanese words for the numbers from one through ten. Some of the words were formatted to fit within a standardized structure, and liberties were taken with their phonetic lithography to account for possible pronunciation shift and language change. Further exploration of historical pronunciations in the Japanese language would be necessary in order to determine if these connections are a reality.

Format: Number. Japanese Pronunciation (Arabic Translation)

- iki (siblings)

- nim (sleep)

- tlzam (need)

- yom (day)

- gowm (covering above earth)

- roquwm (numbers/ideas/opinions)

- schitschi (wet drippy thready rain thing) / na3na (that which a group collectively intends to pass along the comprehension of)

- hat’hcjhiwm (size)

- kyuwm (strength/tolerance/powerful group)

- tohwm (matched pair) / jeuhwm (gathering)

Post Analysis:

If the Japanese for the number two, nin, is matched morphologically to the other pronunciations, it becomes, nim, which means sleep in Arabic.

The kanji for four (四):yon is, visually, very similar to the kanji for day (日): hi/bi in Japanese. The only difference is a 90 degree rotation of the kanji and a slight difference where the strokes connect. Coincidentally, the Arabic word “yom”, means day, comparing very closely with the Japanese.

I initially translated the word for five as numbers arr[q]owm, but that was kind of a stretch. It might also be tents, if it’s being spelled [kh]owm. Either transcription could be possible if the word is looked at physiologically as a glottal stop, and the sounds produced in a similar manner to [g] are extrapolated from the original. As, “gowm,” which I ultimately decided on using as the translation, it means, “clouds,” or, “low-hanging fog.” It may be fruitful to look at the distinction for this entry as a matter of honne (underlying truth in reality) and tatemae (masking surface features of reality), as a cloud of illusion masks the surface of truth.

The word for “thread of a nondescript material” in Arabic is, “schreet,” and the word for, “something-or-other,” is, “shi.” Together, it’s, “schreetshi.” Another Arabic word that used this root is, “sharshir,” meaning, “drip,” or, “drizzle,” like a thread, and, “shiti,” meaning, “rain.” It’s possible that the kanji could represent a rain cloud. An English cognate of that root cluster is, “suture.” There is ample evidence of an initial [Sch], center [r], and word-final [t] sound being present in derivations originating with that root, to enforce that spelling in the transcription.

On the topic of clouds and rain, the kanji for eight looks like a straw rain hat with the top missing. I could not decide if hachi (eight) was the word for need, old man, spelling, or journey/travel, since those words are all homophonically written as hajj/hajji/haji in Arabic. That transcription makes sense because the [jj] and the [ch] sounds are both palatal affricates that can easily be confounded and used interchangeably with the other as languages evolve over time. I only listed the word that shares the personal and historical connotations common and to all three, “hajim.” This particular element on the list, along with the lack of Arabic translation mapping for, “ni,” is what incited the change in encoding of all the numbers to end in an [m] sound. This change seemed to make the translations more palatable in the Arabic sytax. I imagine an elderly person with missing teeth who chewed the ends of their words would end their statements in an m sound, in a pronunciational manner similar to that of an elderly Japanese man singing kabuki (Skip to 21:54 remaining, right after the intro video. We also get a view of the traditional straw rain-hat in this episode), but that’s pure speculation.

Mijeuw means dirtied, or sullied, in Arabic, especially if the physical environment in question, including weather, atmosphere, surface, or form is blackened, grimy, or burned out. It is typically used to describe a person’s body, with the phrase, “ideek mijeuwiyeen,” In Arabic, for example, translating to “your hands are filthy.” Without the affix, [mi], like the original Japanese, and with the addition of the suffix [m], to make it a standard 3-phoneme Arabic root, it simply means gathering.

The Japanese toh, when formatted like the other entries, translates to, “twins,” or, “tohm,” in Arabic, with a strong connotation of a pair of hands.

All of this evidence leads to an initial assessment that the two cultures share some sort of historical linguistic connection, especially when it comes to numbers, which is not impossible given their universality and the manner in which they are passed on from one generation to the next. Migration of populations of humans, and trade along silk and tea roads also enforce the idea that there is a subtle connection between the two languages.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.